Jorge Kanese – vorgestellt von seinem Übersetzer Léonce W. Lupette

Mit der einfachen Meldung, dass man die Gedichte von Jorge Kanese, Dichter aus Paraguay, jetzt auf Lyrikline hören und lesen kann, schien es uns nicht getan. Zu vielschichtig ist dieses Werk, zu komplex auch die Leistung seines deutschen Übersetzers Léonce W. Lupette. Wir freuen uns deshalb sehr, dass Léonce bereit war, uns eine Einführung zu Jorge Kanese, dessen Hintergrund und zu seinen Gedichten sowie deren sprachlichen Besonderheiten zu schicken. Wir bedanken uns sehr herzlich dafür und wünschen viel Freude an der künstlerischen Meisterleistung beider Dichter!

Jorge Kanese (geb. 1947 in Asunción)

Si uno quiere algo bueno, eso cuesta, Kanese dixit: Wenn man etwas Gutes anstrebt, so muss man dafür leiden.1 Gelitten hat Kanese im Gefängnis unter Stroessners Diktatur, wo er gefoltert wurde. Sein Sprechen und Schreiben waren Grund für und sind auch Reaktion auf Inhaftierung und Folter, der Gedichtband Paloma Blanca Paloma Negra (1982) wurde vom paraguayischen Regime verboten. Wer einzig Kaneses Gedichte aus den letzten Jahren liest, diese wilden Mischungen und Mutationen des Spanischen, Portugiesischen, Guaraní und anderer Sprachen, wird vielleicht nicht ohne Weiteres die Schritte erahnen, die dieser berserkerischen, kompromisslosen, radikal-ludischen Ausdrucksweise vorausgegangen sind.

Unter seinen Gedichten aus den achtziger Jahren finden sich sowohl zarte, melancholische Stücke, aus denen persönliche und politische Verlorenheit und Isolation, äußerste Gefährdetheit und Vergänglichkeit sprechen, als auch wütende und witzige Faustschläge. Ansätze einer orthographischen Deformierung und Verwendung einzelner Wörter aus dem Guaraní bietet bereits De gua’u la gente no cambia von 1986. Noch geht es dabei hauptsächlich um das Provozieren, um einen Bruch sowohl mit poetischen als auch mit politischen und gesellschaftlichen Systemen und Schemata. Wut und Unverständnis über eine dekadente, selbstzerstörerische Menschheit und deren Dogmatismen werden von Band zu Band ausgeprägter, ebenso der schwarze Humor, die derbe bis hardchorevulgäre Sprache und die grotesken Bilder und Figuren, nicht selten voller Bezüge auf Philosophie- und Literaturgeschichte, das Widerrufen eines Verses im nächsten. In diesem schonungslosen Bruch mit der Erwartungshaltung einer von jahrzehntelanger, kulturfeindlicher Diktatur geprägten und international isolierten Gesellschaft steckt dennoch etwas Utopisches. Denn was diese Gedichte angreifen, wird mitnichten einem nihilistischen Zerstörungspessimismus preisgegeben; so einfach macht Kanese es sich und seiner Leserschaft nicht. Das Wesen vor allem seiner jüngeren Texte ist radikal lebensbejahend – sie strotzen vor Lust an der Sprache, am Denken, am Dissens.

Gegen Ignoranz, Isolation, Nationalismen, Reinheitsphantasmen und fragwürdige Kanonisierungen behaupten Kaneses Gedichte ein Anderes, indem sie zunächst das scheinbar Naheliegende aufnehmen: die im Triple-Frontera-Raum alltägliche Mischung aus Portugiesisch, Spanisch und Guaraní. An der Grenze zwischen Paraguay und Brasilien wird Portuñol gesprochen, auf den Straßen Asuncións Jopará – eine nicht festschreibbare und von Sprachpuristen verachtete Mischung aus Spanisch und Guaraní. Diese Sprachsituation greift Kanese – eigentlich Canese, aber je nach Buch auch Kanexe oder Xanexe – auf, entwickelt sie weiter, erfindet ein unverkennbares eigenes Sprechen und Schreiben, in das auch italienische Grapheme oder englische Ausdrücke Einzug halten, ebenso wie Worte, die nach Guaraní oder Spanisch oder Portugiesisch klingen bzw. aussehen, die jedoch keiner standardisierten Sprache zuzuordnen sind. Silben und Laute werden gekappt, verdoppelt, verdreht und gedehnt, die Texte werden einerseits in ihrer Verfremdung unzugänglicher; andererseits ist (zumindest den Bewohnern der Triple Frontera) die sprachliche Geste der Mischung aus dem Alltag bekannt, und das Wesen dieser Sprachdeformierung ermöglicht Leserin und Leser außerdem zahllose Assoziationen, ja zwingt geradezu zum wilden Assoziieren, dazu, die Texte lesend in alle möglichen und unmöglichen Richtungen weiterzuspinnen.

In dieser genuin argobrasiguayischen Sprachsituation liegt aber auch das Problem für den deutschsprachigen Übersetzer. Spanisch und Portugiesisch lassen sich gut mischen, weil sie einander so ähnlich sind, und Guaraní und Spanisch haben eine lange gegenseitige Verpfropfungs- und Befruchtungsgeschichte, obwohl es höchst unterschiedliche Sprachen sind. Welche ähnliche Sprache grenzt auch geographisch ans Deutsche? Das Flämische? Oder doch besser das weiter entfernte britische Englisch? Und welche grundverschiedene Sprache gibt es, die in weiten Teilen des deutschsprachigen Raums gesprochen und auf der Straße gar noch gemischt wird? Denn darin bestehen die wichtigen strukturellen, geographischen und historischen Zusammenhänge, die es mitzuübersetzen gilt. Daher die Entscheidung für das Türkische in der Übersetzung: Es ist omnipräsent, in vielen deutschen Städten gibt es Viertel und Geschäfte, deren Schilder, Werbeplakate, Aushänge etc., die zumindest bilingual sind, und auf den Straßen und im Nahverkehr verwenden längst nicht mehr nur noch die türkisch-migrantischen Jugendlichen anatolische Vokabeln. Dieses sehr gestische und kreative Kauderwelsch ist, in vielen Fällen, ebenfalls eine Sprache Ausgegrenzter und Verdrängter, denen keine leicht zu benennende Identität eignet. Darin scheint eine adäquate Analogie zum Jopará zu liegen, vor allem was den performativen Aspekt betrifft, der ja auch Kaneses Gedichte auszeichnet. Das Türkische eignet sich zudem nicht zuletzt auch deshalb, weil es viele Phoneme mit dem Deutschen teilt, sie aber graphisch anders ausdrückt, beide Sprachen zugleich Phoneme und Grapheme kennen, die der anderen jeweils fremd sind – ein Verhältnis, das auch zwischen den von Kanese verwendeten Sprachen besteht und das für seine Schreibpraktiken grundlegend ist.

Zum Weiterlesen: Jorge Kanese: Die Freuden der Hölle, hrsg. u. Übersetzt v. L. Lupette, Wiesbaden: Luxbooks, 2014.

Léonce Lupette, Dezember 2018

1 So Kanese in einem Video bei einem Besuch auf just dem Gelände, auf dem er inhaftiert war und gefoltert wurde. Siehe Webseite zur Aufarbeitung des Stronismo: http://www.meves.org.py/

Léonce W. Lupette (geb. 1986 in Göttingen)

Zum Weiterlesen empfehlen wir

auch die Gedichte von Léonce W. Lupette.

Eine Auswahl findet man auf Lyrikline.

Seit kurzem sind sie dort auch in tschechischer und spanischer Übersetzung verfügbar.

World Poetry Day and an Open Call from Belgium

To celebrate World Poetry Day on March 21, Lyrikline publishes six fine new poets from around the world between March 19-21 (find all their names below).

Laurence Vielle

One of them is Wallonian poet Laurence Vielle, the first poet contributed by our new Wallonian network partner L’Arbre de Diane.

Laurence was the Belgian National Poet until Els Moors took over in January of 2018. Now Els Moors has started an open call in connection with World Poetry Day:

Adopt your city with a poem

On the 21st of March, World Poetry Day, the National Poet of Belgium, Els Moors, invites all people worldwide to gather their most beautiful odes and elegies on their cities (/ countries / states / …) and make them public. In times of gentrification, mass tourism and worldwide migration we are craving for lonely flâneurs and notorious wanderers who want to lay bare the mysterious heart of their cities. Are you still in love with the city you were born in? Were you pushed on by love, or obliged to leave your hearth and home? Adopt your city by writing an urban elegy and take part in the writing of the most exotic Lonely Planet at this time: The adopted cities.

Would you like to contribute to this special worldwide anthology, and motivate others to join?

Then join this action in a few steps:

1. Publish your own poem on our page starting the 21st of March 2018: www.adoptedcities.be

2. Post your poem on all your possible (social) media and encourage fellow citizens to adopt a city with a poem and to join the action. Everybody can share their city-poem on our website. On Facebook, please use #adoptedcities so we can follow and share your posts.

3. Enjoy an easily accessible and interactive online anthology, a playful way to motivate people to read and write poetry!

Els Moors

Read the poems of Els Moors, “Dichter des Vaderlands” of Belgium here. Read the city poem of her predecessor and ambassador Laurence Vielle here.

We would – very much – like people from all over the world to take just a minute to think about poetry (and all its modern interpretations) and to write even a short piece of poetry. Let’s make a tribute to poetry and to our world together!

We hope that many people out there follow Els Moors’ call to post poems. We’d also like to invite you to discover the other new voices that we published on the occasion of this year’s World Poetry Day, next to Laurence Vielle:

M. NourbeSe Philip (Tobago/Canada)

Sukrita Paul Kumar (India)

Benjamín Chávez (Bolivia)

Ketty Nivyabandi (Burundi/Canada) and

Yoko Tawada (Japan/Germany).

Happy World Poetry Day!

Poetry from India

With the start of 2018 we’ll be able to present more poetry from India on Lyrikline thanks to a newly established partnership in India. The Enchanting Verses Literary Review and poet and editor Sonnet Mondal as its country-editor for India take care of the selection and recording of new Indian poets. Their first contribution to Lyrikline is poet Anju Makhija and we’re glad that more new voices are already being prepared.

Many thanks to Sonnet Mondal not only for his efforts in presenting Indian poetry but also for an insight into poetry in India he compiled, giving us an idea about the developments from the beginning to today, the diversity of languages and the various traditions of this rich poetry universe of India.

Poetry from India (by Sonnet Mondal)

The literary history and tradition of India spins around poetry. From the Vedic times to the 21st century, Indian poetry has come a long way through epics, cultural intersections, conquests, devotion, local dialects, and festivals. Vedvyasa’s Mahabharata, considered as the longest epic poem in the world is so huge that there’s a saying — ‘What’s missing in the Mahabharata doesn’t exist in India’. With 110,000 couplets in eighteen sections — this epic is about seven times the combined length of Homer’s the Iliad and the Odyssey. Other India epics that substantially used poetry as the medium of expression were — Valmiki’s Ramayana, Māgha’s Shishupala Vadha, Māgha’s Kiratarjuniya, Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita and Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda. Even in these times — poetry flourished in other languages — in other parts of the country. The Sangam literature era — from 300 BC to 300 AD contains about 2381 poems in Tamil composed by 473 poets from diverse backgrounds. The Bhakti movement during the 15th and 17th century AD saw an emergence of devotional poetry, the influence of which still remains contemporary. Influenced by Vedic beliefs — the works of poets like Andal, Kabir, Tulsidas, Ramananda, Tukaram, Mirabai, and Narsinh Mehta still remain a muse of the post-post modern period.

Though most of the early Indian poetry appeared in Sanskrit — there was a shift in course of language towards the medieval period. Amir Khusrau penned mainly in Persian, but composed almost half a million verses in Persian, Turkish, Arabic, Braj Bhasha, Hindavi as well as the Khadi Boli. Later Hindus started writing in Persian and this led to the development of Indo-Persian literature. The Abd-Allāh cites over 130 names of Hindu-Persian poets who lived in the late 18th and 19th century. The first evidence of a Hindu writing Persian poetry is attributed to a Brahmin named Pandit Dungar Mal. In late 17th century — Sikhs also started contributing to the Persian poetry of India, and Guru Gobind Singh himself wrote an extensive Persian poem — Zˈafarnāma.

From Jayadeva in 12th century and Amir Khusrau in the 15th century, to Michael Madhusudan Dutt and Tagore in the 19th Century, poetry in Indian vernaculars reigned supreme. The father of Bengali Sonnet, Michael Madhusudan Dutt brought a revolution by penning the famous tragic epic — Meghnad Bodh Kavya and also by introducing blank verse in Bengali poetry.

The local and regional languages first encountered English in the beginning of the 18th century — with the break-up of the Mughal empire to British India. The first Nationalist Poet of Modern India- Henry Louis Vivian Derozio — considered the father of Indian English Poetry wrote in English and was much influenced by the English Romantic poets. Tagore translated his own work into English — in his book Gitanjali. Later, Nissim Ezekiel and A.K. Ramanujan wrote much under the influence of post-war American Poets and some British poets like Wilfred Owen. Ramanujan travelled to America in 1959 and stayed in Chicago until his death in 1993. He wrote profusely during these years. Indian English poetry- from Derozio and Toru Dutt through Nissim Ezekiel, A.K. Ramanujan and Jayanta Mahapatra to present day poets is recognized worldwide. It has come up as a form that has its own tradition, lyrical quality, approach, delivery and style. Inspite of the surge of Indian English literature, regional language literature through the hundreds of languages spoken in India today — has remained close to the hearts of readers. Regional languages in the country has given rise to many countries within one country bounded by boundaries without lines. Regional poetry in India, allows an insight into the diverse depictions and presentation of same things by different regions of India.

Delving into Indian poetry, is like descending an age old cave in search of minerals, wall arts and history. Selecting poets for Lyrikline cannot be all inclusive but there would be a constant quest to include the best contemporaries from various Indian languages.

Sonnet Mondal, photo: John Minihan

Sonnet Mondal is the author of Ink and Line and five other books of poetry. Winner of the 2016 Gayatri Gamarsh Memorial Award for literary excellence, Mondal was one of the authors of the ‘Silk Routes’ project of the IWP, University of Iowa, from 2014 to 2016. He is the editor-in-chief of the Enchanting Verses Literary Review, and lives in Kolkata.

Corresponding Texts – Translation as a Call and Response

When translator Sharmila Cohen sent lyrikline her translations of Marion Poschmann’s cycle of poems “künstliche Landschaften“, what we received was much more than a mere translation.

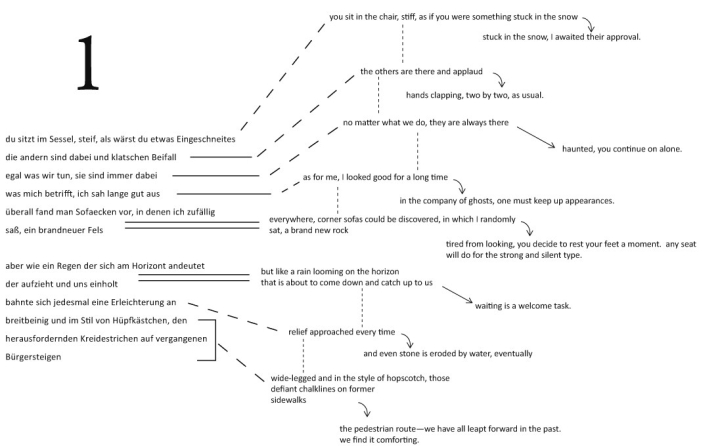

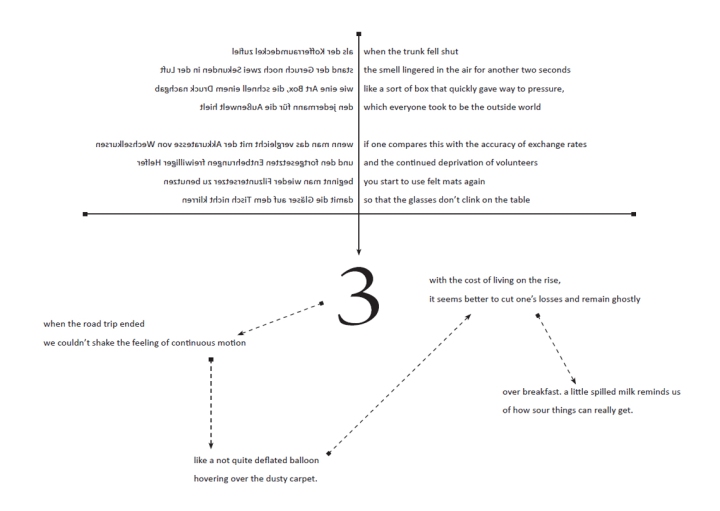

Marion Poschmann’s künstliche Landschaften 1 / articifical landscapes 1 ©Sharmila Cohen

We found these experimental visualised texts so intestesting that we asked Sharmila if we could publish them here on our blog and she agreed.

Marion Poschmann’s künstliche Landschaften 2 / articifical landscapes 2 ©Sharmila Cohen

Sharmila Cohen on this project:

This series is part of a project that investigates poetry translation as a correspondence between author and translator. For this translation, I took Marion Poschmann’s original poems and translated them in two ways: first by attempting to faithfully retain as much of the original content from the German version as possible; and then by writing new poems that directly responded to each of her texts. In this way, non-German-speaking readers gain insight into the German text through these two distinct vantage points. There is also a third sort of “translation” going on here: a visual representation of the translation act itself. Using various design elements, I attempted to show the movement and relationship between all three versions of each text, depicting a sense of call and response, as well as enforcing the notion of creative translation as an evolving form of interpretation.

Marion Poschmann’s künstliche Landschaften 3 / articifical landscapes 3 ©Sharmila Cohen

About the translator:

Sharmila Cohen lives in Berlin, where she initially moved on a Fulbright Scholarship to investigate poetry in translation and now works as a freelance writer, translator, and editor. She is a co-founding editor of the translation press Telephone Books. Her work can be found in Harper’s Magazine, Circumference, and Epiphany, among other places.

Marion Poschmann’s künstliche Landschaften 4 / articifical landscapes 4 ©Sharmila Cohen

German poet Marion Poschmann was asked to be this year’s lyrikline curator, tasked with selecting four German speaking poets to be recorded for the website in 2017. She will introduce her selections at an event at Haus für Poesie in Berlin on November 16, 2017.

Marion Poschmann’s künstliche Landschaften 5 / articifical landscapes 5 ©Sharmila Cohen

Petr Borkovec zur tschechischen Lyrik der letzten zwanzig Jahre

Petr Borkovec (*1970) ist ein weit über Tschechien hinaus geschätzter Dichter. Wir kennen ihn, seit er 2004 als Gast des Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD nach Berlin kam. Fast genauso so lange kann man seine Gedichte schon auf lyrikline hören; nun um 5 neue, 2017 aufgenommene Gedichte erweitert.

- Foto: Dirk Skiba

Petr organisiert in Prag die Lesungen des Café Fra und war u.a. Kurator der deutsch-tschechischen Lyrik-Reihe Im Hier und Jetzt des Goethe-Institut Prag. Er hat einen exzellenten Überblick über aktuelle Poesie und 2012 einen lesenswerten Essay zur tschechischen Lyrik der letzten 20 Jahre geschrieben, den es inzwischen auch in deutscher Übersetzung gibt. Wir danken unserem tschechischen Lyrikline-Partner für den Hinweis auf diesen Essay und dem Autor und dem Goethe-Institut Prag dafür, dass wir ihn hier veröffentlichen dürfen. (Den tschechischen Originaltext findet man unterhalb der deutschen Übersetzung.)

Die Begegnung mit den Arbeiten eines jungen Dichters lässt den Lyriker Petr Borkovec über die tschechische Lyrik der letzten zwanzig Jahre nachdenken.

Heute habe ich einen Brief mit Gedichten bekommen, von einem Autor, der 1990 geboren wurde. Die Gedichte sind, glaube ich, gut, einige sind mir sehr nahe, bestimmt werde ich was davon drucken. Der Dichter wurde in dem Jahr geboren, in dem ich mein erstes Buch veröffentlicht habe. Beide sind also gleichalt. Es wäre so schön, sage ich mir, wenn ich seine Lyrik überhaupt nicht verstünde, spüren würde, wie fern sie mir in jeder Hinsicht ist, und gleichzeitig von ihr fasziniert wäre, ihr verfiele. Doch das passiert nicht. Ich lese sie, wähle aus, sortiere, ordne, einige Gedichte lege ich beiseite. Entweder ist aus mir ein literarischer Routinier geworden (was wahrscheinlich ist) oder die tschechische Lyrik hat sich in den letzten zwanzig Jahren nicht allzu sehr verändert.

Ich weiß es nicht. Normalerweise denke ich darüber nicht nach.

Vor zwanzig Jahren…

Kein Dichter hat hier in diesen zwanzig Jahren literarisch Revolution gemacht und die tschechische Dichtung in eine unerwartete und unerforschte Richtung gewendet, das ist wahr. Aber wollte das jemand? (more…)

Poetry from Burundi

By Adams Sinarinzi of Ubuntu Advocates Initiative, the Lyrikline partner organisation in Burundi

Presenting poetry from Burundi is not an easy task. T.S. Eliot seemed to think true poetry is hardly translated, and one needs to truly sense where those words are from. Until the emergence of the modern, there was no need of presentingpoetry, for poetry was part of life.

….do you feel her drive?

Look at his eyes,

Do you read his verse? [1]

But the unity of life, some will say, was lost with the last myth and cosmic societies, that Burundi belonged to until a century ago. Dissolved by the increasing requirements of the modern world, several separate and independent spheres were born. One of them, the arts and culture, has grown (often unwillingly) to acquire the function of precisely representing the lost unity.

Beyond their powers to express the various contradictions and sensitivities, the world literature offers us symbolic levers for an understanding and appropriation of our lives. The young contemporary Burundian literature is best understood in this context, which is of an attempt to understand its environment and express its sensibility to the world.

In his academic book La Littérature de langue française au Burundi, [2] Professor J. Ngorwanubusa of the University of Burundi regrets however the few avenues for the literature of Burundi. There is barely any publishing house; a few reviews had been existing in the 1960s and 1970s but never survived except a few Christian reviews run by a few members of the Burundi Catholic Church.

But the interested literary person won’t miss the corners behind the central market where the old (often stolen!) books are sold, the oldest book storeLibrairie St Paul, or the French cultural center (whose interesting café hosts the unfortunately more and more penniless intellectuals in the city!) and of course the newly opened Lire Africa in Gallerie Alexander, specializing in fiction from Africa. A blog by the poet Thierry Manirambona (“la plume burundaise”) lists an impressive archeology of Burundian books old and new, and a few poets do publish their poetry directly on the internet as the acclaimed Ketty Nivyabandi.

Poetry in print might be hard to find in the country, but if you are insisting you will discover the underground intellectual and literary scene of the marvelous Café literaire Samandari that meets every Thursday evening at the Burundi Palace right in the middle of the city center. But one should say they met there, for since a year now these meetings are no longer held. (more…)

Map of a Thousand Lives – A Brief Introduction to Poetry in Malaysia

By Pauline Fan of Kala, the Lyrikline partner organisation in Malaysia

An attempt to chart the origins and evolution of modern poetry in Malaysia unearths complex historical processes and cultural interactions that have shaped contemporary Malaysian society. To speak of the writing of poetry in Malaysia, one must grapple with – or at least try to imagine – the essentially pluralist and polyglot nature of its people as well as the changing socio-cultural landscape, where “the map of a thousand lives will be seen* ”.

Malaysia is a country where at least four main languages predominate – Malay, English, Chinese and Tamil, further punctuated by a multitude of dialects and colloquialisms according to clan or region. The multicultural and multilingual population of the Malay Peninsula has been evident since at least the 15th century, when the Sultanate of Malacca rose to become one of the most thriving entrepôts in Asia, drawing merchants, scholars, and envoys from neighbouring kingdoms and faraway empires alike. Successive waves of immigrants from all over the Malay Archipelago, China, and India – some of whom settled, intermarried, and formed new distinct communities and cultures such as the peranakan or Straits-born communities – added yet more layers to the inextricable diversity of Malaysian society.

The conquest of Malacca by Portuguese (1511) and Dutch (1641) imperial powers preceded British colonial control, and later the Japanese occupation, of the Malay Peninsula and the northern provinces of Borneo. Each of these imperialist presences left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of Malaysia, including on the Malay language in the case of Portuguese, Dutch and English, adding to the vast compendium of loanwords in Malay from Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Tamil, and Chinese. The Malay language served as a lingua franca for the Malay Archipelago for centuries, and forms the basis of the standardised national languages of both Malaysia (Bahasa Malaysia) and Indonesia (Bahasa Indonesia), mutually intelligible with some differences in vocabulary and spelling.

Oral traditions and pan-Malay poets

The origins of Malay-language poetry can be traced to the vast and various oral traditions that have been cradled in the Malay Archipelago as well as classical Malay texts known as Hikayat that date back as far as the 14th century. Traditional Malay poetic forms include the syair, the pantun, the gurindamand seloka, all of which are found in both oral and written literature. While traditional or classical, many of these poetic forms are intrinsically innovative, urging improvisation and spontaneous composition. The pantun, for instance, was sometimes performed as balas pantun, a call-and-response ‘duel’ or ‘flirtation’ between two poets, especially during performances of the Dondang Sayang (love ballads) of Malacca. (more…)

Poesie und Performance (2) – Lesungen und O-Töne

Dass Autorinnen ihre Gedichte vorlesen erscheint uns als Selbstverständlichkeit – doch was passiert eigentlich in dem Moment in dem eine Dichterin ihre eigenen Texte einem Publikum vorliest? Wir begleiten Carolin Callies bei der Lesung ihrer Gedichte im Tonstudio der lyrikline und auf der Bühne der Literaturwerkstatt Berlin.

>>> [a playlist for World Poetry Day 2016] studio highlights

Im Vortrag bekommt der Zuhörer jenseits der individuellen Stimm- und Klangfarbe der Dichterin noch sehr viel mehr zu hören. Hier werden die klanglichen Aspekte eines Gedichtes transportiert, seine lautlichen Bezüge und rhythmischen Strukturen. Reime, Assonanzen und Alliterationen entfalten ihre ganze Wirkung, strengere Strophen- und Gedichtformen geben ihren Aufbau hörbar preis. Der O-Ton einer Dichterlesung beinhaltet viele spannende Aspekte, in die man sich hörend vertiefen kann: Wie geht der Dichter seinen Gedichtvortrag an? Was lässt er mitschwingen, was bringt er an Stimmung, Intensität und Pathos mit ein? Wie setzt er die Pausen, wo den Spannungsbogen? Wo folgt der Dichter seinem Ausgangstext, wo überlässt er sich dem Textfluss, wo gerät er ins Stocken, wo kontrastiert er ihn vielleicht? Insbesondere auf lyrikline, wo das Hören einer Dichterstimme zu einem ganz intimen Moment werden kann, lassen sich die angesprochenen Aspekte nachhören und wiederholen, so oft man will.

Was passiert aber mit dem Gedicht, wenn es durch seine Autorin vorgelesen wird? Die folgenden Sichtweisen demonstrieren, wie unterschiedlich ein Verständnis von Lyrik sein kann.

Ein weit verbreitetes Verständnis des Verhältnisses von Gedicht, Autorin und Publikum lässt sich auf folgende Aussagen reduzieren:

>> Das geschriebene Gedicht ist ein abgeschlossenes Werk und unveränderlich.

>> Jeder Vortrag des Gedichts ist eine Interpretation, die von einem Original ausgeht.

>> Der Autor hatte eine bestimmte Intention, die er durch die Mittel des Vortrags herausarbeiten kann.

>> Das Gedicht kann durch den Vortrag des Autors besser verstanden werden, weil dieser es seiner Intention entsprechend richtig interpretiert.

Ein performativer Ansatz dagegen begreift sowohl den Entstehungsprozess eines Gedichts als auch das Ereignis des Vortrags als etwas, dem man schon einen eigenen künstlerischen Charakter zuweisen kann:

>> Das Gedicht ist nicht der niedergeschriebene Text, sondern realisiert sich allein im Vorgang des Schreibens, des Lesens und des Vorlesens.

>> Die Lesung selbst ist mit all ihren Zufälligkeiten und Abläufen ernst zu nehmen. Raum und Zeit gehören zur ästhetischen Erfahrung dazu.

>> Damit ist die Bedeutung des Gedichts nicht fest, sondern situationsabhängig. Statt Interpretationen lassen sich Inszenierungen feststellen, die sich auf kein eigentliches Original mehr beziehen. Was eine gute Inszenierung ausmacht legen ihre eigenen Maßstäbe fest, die immer wieder neu verhandelt werden müssen.

>> Die Rezipientinnen müssen nicht länger versuchen zu verstehen, was der Autor eigentlich sagen wollte. Ihr eigenes ästhetisches Erleben des Gedichts ist der Ausgangspunkt für eine Auseinandersetzung.

Das Entscheidende sowohl bei einer Live-Lesung als auch beim Anhören einer Playlist auf lyrikline ist, dass die Autorin selbst liest. Dass dies zwangsläufig die beste Weise ist ein Gedicht zum Sprechen zu bringen, ist jedoch keine Selbstverständlichkeit, sondern hängt von dem individuellen Verständnis von Lyrik ab, das sich neben den vorgestellten Positionen natürlich auch noch in ganz anderen Weisen zusammensetzen kann.

Lyrik-Empfehlungen 2016

Welche Gedichtbände sind besonders bemerkenswert, interessant, überraschend? Kritiker, Lyriker und Vertreter literarischer Institutionen empfehlen zwölf deutschsprachige und zwölf ins Deutsche übersetzte Gedichtbände – ausgewählt aus den Neuerscheinungen von Anfang 2015 bis März 2016.

Abgegeben haben die Empfehlungen in diesem Jahr: Michael Braun, Heinrich Detering, Ursula Haeusgen, Harald Hartung, Florian Kessler, Michael Krüger, Kristina Maidt-Zinke, Holger Pils, Marion Poschmann, Monika Rinck, Daniela Strigl und Thomas Wohlfahrt.

Lyrik-Empfehlungen 2016 – Deutschsprachige Lyrik

• Gerd Adloff: zwischen Geschichte und September. Corvinus Presse, Berlin 2015

• Christoph W. Bauer: stromern. Haymon, Innsbruck 2015

• Daniel Falb: CEK. kookbooks, Berlin 2015

• Swantje Lichtenstein: Kommentararten. Verlagshaus J. Frank, Berlin 2015

• Andreas Neeser: Wie halten Fische die Luft an. Haymon, Innsbruck 2015

• Daniela Seel: was weißt du schon von prärie. kookbooks, Berlin 2015

• Anne Seidel: Chlebnikov weint. Poetenladen, Leipzig 2015

• Armin Senser: Liebesleben. Edition Lyrik Kabinett, Hanser, München 2015

• Volker Sielaff: Glossar des Prinzen. luxbooks, Wiesbaden 2015

• Julia Trompeter: Zum Begreifen nah. Schöffling & Co., Frankfurt a. M. 2015

• Christoph Wenzel: lidschluss. Edition Korrespondenzen, Wien 2015

• Ror Wolf: Die plötzlich hereinkriechende Kälte im Dezember. Schöffling & Co., Frankfurt a. M. 2015

Lyrik-Empfehlungen 2016 – Lyrik in deutscher Übersetzung

• Henry Beissel: Flüchtige Horizonte. Aus dem Englischen von Heide Fruth-Sachs. LiteraturWissenschaft.de (Transmit), Marburg a. d. Lahn 2016

• Anna Maria Carpi: Entweder bin ich unsterblich. Aus dem Italienischen von Piero Salabè. Edition Lyrik Kabinett, Hanser, München 2015

• Jon Fosse: Diese unerklärliche Stille. Aus dem Norwegischen von Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel. Kleinheinrich, Münster 2015

• Federico García Lorca: Liebesgedichte. Aus dem Spanischen von Ulrich Daum. Rimbaud, Aachen 2016

• Bengt Emil Johnson: Das Fest der Wörter. Aus dem Sumpf. Aus dem Schwedischen von Lukas Dettwiler. edition offenes feld, Dortmund 2015

• István Kemény: Ein guter Traum mit Tieren. Aus dem Ungarischen von Orsolya Kalász und Monika Rinck. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2015

• Itzik Manger: Dunkelgold. Aus dem Jiddischen von Efrat Gal-Ed. Jüdischer Verlag / Suhrkamp, Berlin 2016

• Kate Tempest: Hold Your Own. Aus dem Englischen von Johanna Wange. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2016 (Erscheinungstermin wurde auf Juni verschoben.)

• Eugeniusz Tkaczyszyn-Dycki: Tumor linguae. Aus dem Polnischen von Michael Zgodzay und Uljana Wolf. Edition Korrespondenzen, Wien 2015

• Rosmarie Waldrop: Ins Abstrakte treiben. Aus dem Amerikanischen von Elfriede Czurda und Geoff Howes. Edition Korrespondenzen, Wien 2015

• William Wordsworth: Gedicht, noch ohne Titel, für S. T. Coleridge (The 1805 Prelude). Aus dem Englischen von Wolfgang Schlüter. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2015

• Jeffrey Yang: Yennecott. Aus dem Amerikanischen von Beatrice Faßbender. Berenberg, Berlin 2015

Die Lyrik-Empfehlungen werden jährlich zur Leipziger Buchmesse veröffentlicht. Sie werden herausgegeben von der Deutschen Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung, der Stiftung Lyrik Kabinett und der Literaturwerkstatt Berlin/Haus für Poesie in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Deutschen Bibliotheksverband. Gefördert von: Deutscher Literaturfonds

Die ausführliche Broschüre finden Sie in der Anlage.

Im Internet unter: www.lyrik-empfehlungen.de

Lesungen zu den Lyrik-Empfehlungen finden am 18. März in Leipzig und am 23. März in Berlin statt. Zum Welttag der Poesie, am 21. März, werden die empfohlenen Lyrikbände in Bibliotheken und Buchhandlungen präsentiert.

Veranstaltungen zu den Lyrik-Empfehlungen 2016

Freitag, den 18. März 2016

15 Uhr: Buchmesse Leipzig

Forum Literatur, Halle 4: Stand E101

mit den Autoren Daniela Seel, Anne Seidel, Volker Sielaff und Julia Trompeter

vorgestellt von Michael Braun, Literaturkritiker, Florian Kessler, Journalist, Kristina Maidt-Zinke, Kulturjournalistin, Holger Pils, Stiftung Lyrik Kabinett, Marion Poschmann, Autorin, und Thomas Wohlfahrt, Literaturwerkstatt Berlin/Haus für Poesie

20 Uhr: Gohliser Schlößchen

Menckestraße 23, 04155 Leipzig Nord

mit den Autoren Daniel Falb, István Kemény, Volker Sielaff und Christoph Wenzel

vorgestellt von Michael Braun, Literaturkritiker, Katharina Narbutovi, Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD, Holger Pils, Stiftung Lyrik Kabinett, und Thomas Wohlfahrt, Literaturwerkstatt Berlin/Haus für Poesie

Mittwoch, den 23. März 2016

19 Uhr: Literaturwerkstatt Berlin/Haus für Poesie

Knaackstraße 97 (Kulturbrauerei), 10435 Berlin

Eintritt: 6/4 Euro

mit den Autoren Swantje Lichtenstein, Eugeniusz Tkaczyszyn-Dycki und Christoph Wenzel

vorgestellt von Holger Pils, Stiftung Lyrik Kabinett, Marion Poschmann, Autorin, und Thomas Wohlfahrt, Literaturwerkstatt Berlin/Haus für Poesie

Interviews on “poetry & refugees” for World Poetry Day 2015

It has become a tradition over the past years that we use World Poetry Day on March 21 to focus on a specific aspect or topic of the poetry world. The situation of refugees has a sad currentness all over the world today and it affects also poets, in their personal life and in their writing.

We asked a handful of “lyrikline-poets” who have a personal relation to this topic to answer a written interview to share their ideas and experiences. Each of the poets got a questionnaire and was

free to chose from a range of questions. The answers that reached us are remarkable, important, and moving and we would like to thank all the poets very much for openly speaking about their opinions and events in their life.

Thank you:

Ali Al-Jallawi

Ghayath Almadhoun

Fiston Mwanza Mujila

Mansur Rajih

Marie Silkeberg

Sjón

Diana Vallejo

You can read each interview in an own blog article and we hope you’ll find them as enriching as we do. Have a good World Poetry Day and “Listen to the Poet!”

leave a comment